It’s a bewildering sight. Athletes seemingly in peak physical condition collapsing

without warning. Though rare, sudden cardiac death is still considered the leading

medical cause of death among athletes — especially young adults.

Many times, the medical event can be traced back to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a genetic disease that causes the heart to contract more than it should. This leads to thicker than normal heart muscle, which impairs blood flow and makes it harder for the heart to pump blood. Affecting an estimated 1 in 500 people in the U.S., it’s the most inherited heart disease, according to the American Heart Association.

However, University of North Texas research could be key to developing more effective treatments for HCM in the future. It’s work that’s been more than a decade in the making for UNT biochemist Dr. Douglas Root, associate professor of biological sciences who specializes in the molecular structure of muscles and proteins.

“There is a drug on the market that can treat HCM, but it doesn’t really work well for young adults, so we still need more drugs along these lines,” Dr. Root says. “We hope our research can be a foundation to develop potential treatments that will be effective for more people with this disease.”

Root’s College of Science colleague Dr. Amie Lund examines an unseen foe for cardiovascular health — air pollution. In mechanical engineering, Hamid Sadat and his team developed a computational model to better understand how calcific aortic valve disease occurs. In biomedical engineering, Dr. Fateme Esmailie is using artificial intelligence and 3D-printed models to study cardiovascular fluid dynamics, and Dr. Huaxiao “Adam” Yang’s is creating organoids to advance a tissue engineering system for modeling and treating cardiovascular diseases.

Collectively, the research from UNT experts, funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association and others, is producing a much deeper understanding of the heart and could contribute to more effective treatments for heart diseases — the leading cause of death in the U.S. for more than 100 years.

A New Peptide

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy happens when people have mutations in the genes that are responsible for heart muscle protein production.

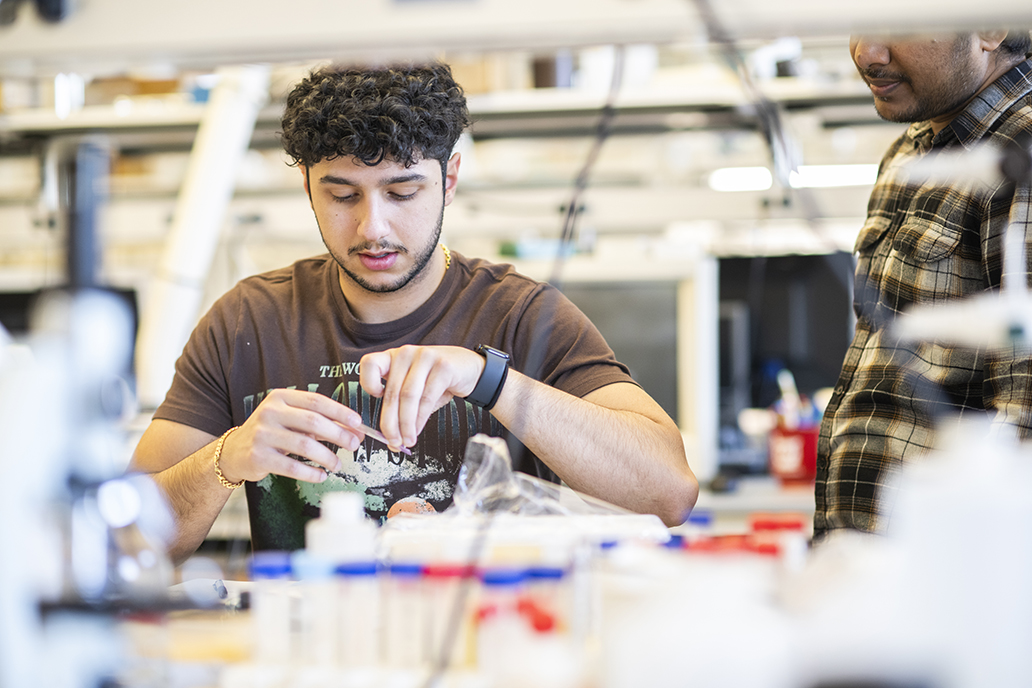

“Those mutations make the protein structure less stable,” Dr. Root says. “So, this particular peptide that we’ve designed will bind to the protein myosin filament strands in heart muscle to hold them together and make them more stable,” says Root, whose research has been funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and most recently by the NIH.

For his NIH-funded project investigating the new peptide to help with HCM, Dr. Root has worked with researchers at King’s College London, University of Kentucky, University of Missouri and Washington State University in Pullman.

“We designed the peptide at UNT, and our collaborators have helped us develop it further

and test it,” says Dr. Root, who is the named inventor on a pending U.S. patent for

the peptide.

“We designed the peptide at UNT, and our collaborators have helped us develop it further

and test it,” says Dr. Root, who is the named inventor on a pending U.S. patent for

the peptide.

Fundamental research for the novel peptide has been ongoing since 2011 at UNT. Alysha Joseph (’13) contributed to the work as a teenager in UNT’s Texas Academy of Mathematics and Science, which encourages its students to get involved in research at the university. It was her first experience with scientific research and inspired her current career journey.

“I had results that were somewhat positive and promising after my time in Dr. Root’s lab, but in my mind at that time, clinical translation seemed like a faraway dream,” says Joseph, who recently talked with Root about being named a co-author on a forthcoming paper including research she completed as a TAMS student.

Now a first-year cardiology fellow at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Joseph has continued her interest in HCM and the study of the heart. During her combined residency in internal medicine and pediatrics, she examined outcomes of patients who were born premature and how it affects their hearts as they get older.

“We know that hearts in people born prematurely tend to be smaller and stiffer,” Joseph says. “And over time, they can develop pulmonary hypertension and diastolic heart dysfunction. Knowing this population is at risk for these problems earlier in life, we could start screening them at a younger age to hopefully prevent these complications.”

Unseen Foe

Dr. Amie Lund, UNT associate professor of environmental toxicology, is hoping her research can help prevent heart problems for people down the road as well. She has conducted research related to the heart for more than 20 years — supported by millions of dollars in grants from the NIH and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“The heart is often thought of as just a pump, but its proper function is critical to life, providing the oxygen and nutrients that our cells need to survive,” says Dr. Lund, who is director of UNT’s Advanced Environmental Research Institute, which unites researchers across disciplines for projects focused on mitigating environmental problems in the world.

“The heart is often thought of as just a pump, but its proper function is critical to life, providing the oxygen and nutrients that our cells need to survive."

-Dr. Amie Lund, associate professor of environmental toxicology

It’s well documented that genetics, diet and lifestyle can impact heart health, but Dr. Lund’s lab asks questions about how exposure to common environmental air pollutants can contribute to a range of health problems from obesity to cardiovascular disease.

“For the last 30 years, we’ve known that on days of high air pollution, we see a higher incidence of heart attacks and strokes,” Dr. Lund says. “We have the clinical data to back that up, but we still don’t fully understand what’s happening in blood vessels and in the heart that contributes to these conditions. And so, our research investigates how exposure to these air pollutants can lead to these outcomes in the body.”

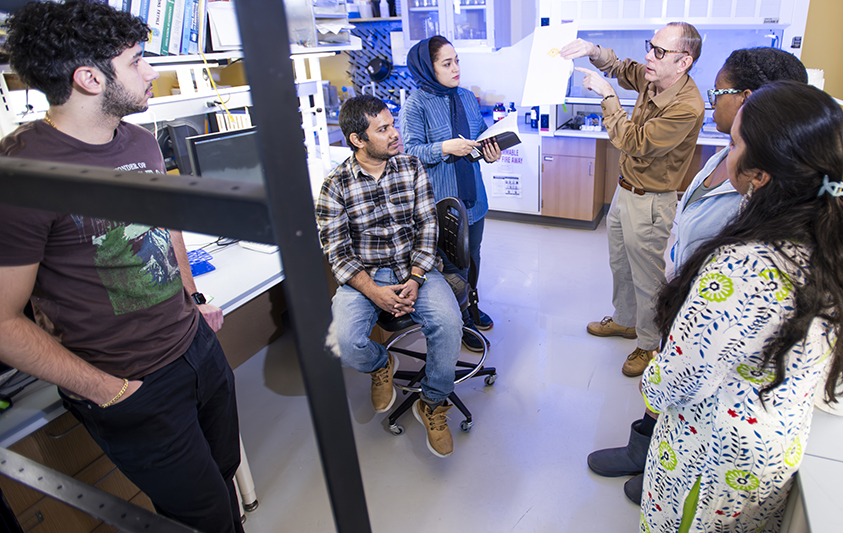

In urban areas such as the North Texan region, a major culprit causing poor air quality is pollutants generated from vehicles on the road, she says. That’s why Dr. Lund and her team of researchers, such as Honors College biology student Kennedy Stevens, are examining how pollutants like car exhaust are altering signaling pathways in the body. Specifically, they’re looking at the renin-angiotensin system, which is responsible for regulating blood pressure.

“We’re trying to tease out which of these signaling pathways in our body could possibly be a target for a pharmaceutical prevention or therapy,” Dr. Lund says. “And more importantly, if we know which components coming out of our vehicle exhaust that are particularly harmful to our bodies, then there is evidence to advocate for policy change that could reduce human exposure to these pollutants.”

Stevens (pictured third from right) investigates whether exposure to exhaust can cause

the production of inflammatory proteins in the heart, which indicate early development

of cardiovascular disease.

Stevens (pictured third from right) investigates whether exposure to exhaust can cause

the production of inflammatory proteins in the heart, which indicate early development

of cardiovascular disease.

“I really like the applications that biology can have to improve the health of people,” says Stevens, who wants to become a research scientist after graduation, possibly working in the pharmaceutical industry or for the government. “That’s what drove me to join Dr. Lund’s lab because the research we’re doing now could have real-life implications.”

Read more about heart research at UNT via Research and Innovation